Brandan P. Buck

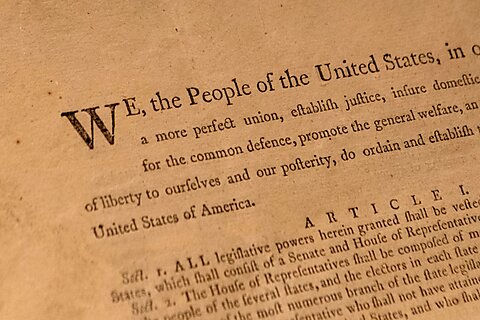

Fall may finally have arrived in DC, but one discussion that never seems out of season is pontificating on a need for a return of military conscription. While the leaves may have turned, the substance of the case from those who advocate for conscription remains the same: blending arguments of geopolitical necessity and socio-cultural improvement, arguing that such an institution “would contribute to maintaining the integrity of our domestic political life.”

As radical as such an idea may sound, it has gained traction in recent months. And even when dressed with a veneer of moderation, it still holds alarming potential for undermining American liberty. Such was the case for the Center for a New American Security’s (CNAS) June report, “Back to the Drafting Board.” Part of what author and activist Edward Hasbrouck quipped was the “summer of the draft,” CNAS’s report advocated for an overhauled Selective Service System (SSS) to serve as a backstop for enabling total military mobilization and as a deterrent against the near-peer competitors.

While the paper noticeably and laudably eschewed two traditional talking points, namely the use of the draft as a domestic political tool and as a means of coercive recruitment for peacetime, the proposal by authors Katherine L. Kuzminski and Taren Sylvester should cause alarm for those who value liberty and restrained government.

Chief among their ideas was an overhauled registration system that would collect personal data beyond the current limits of one’s name, Social Security number, and address. Kuzminski and Sylvester claim that the changing nature of war requires a 21st-century military with diverse skill sets, arguing that the All-Volunteer Force (AVF) “could further benefit from the use of conscripts who bring technical skill sets not readily available in the professionalized force.” They propose, as other draft proponents have argued, that a future American military would need its share of keyboard warriors too, and only a draft could adequately field such a force.

To prepare for such a requirement, the authors assert that “the federal government would benefit from additional information, including educational attainment, chronic medical conditions precluding military service, skill sets, and preferences regarding assignment to the military services and career fields or military occupational specialties.” In short, Uncle Sam would need to build dossiers on every American man (and possibly every American woman) from 18–26 and maintain them via a virtual panopticon, the like of which the US has never constructed before.

Putting the moral arguments aside for a second, such data collection requirements would pose a logistical nightmare for a federal government that has continually proven itself inept at protecting the private information of its citizens. Such collection efforts look nearly impossible, for as author Edward Hasbrouck has noted, current SSS databases are woefully neglected, with dead addresses and other shortcomings. This raises the question of enforcement: how do Kuzminski and Sylvester propose to enforce such requirements? We do not know because they do not tell us.

Enforcement is a glaring oversight on their part despite acknowledging that “a higher percentage of Americans would object to compulsory service in a future scenario than in the past—even higher than the rate of protests seen during the Vietnam War,” a commonly held view for a conscription exercise, the results of which lay at the heart of their article.

Back to the drafting board, indeed.

Additionally, because most initial selective service enrollees would conceivably have very similar educational training and skills, they would have to regularly update their information with the SSS for such a database to be effective. This requirement would insert the federal government into the lives of every American citizen, placing them as a target of constant surveillance.

Finally, in their report, they note that social media “has the potential to play a role in American compliance with future draft mobilization,” using Washington’s latest buzzword, “disinformation.” The implications here, of course, are disturbing, yet another casus belli for undermining the First Amendment through social media regulation.

Past opponents of conscription argued that the practice would turn America into a garrison state. Whether in war or peace, Kuzminski and Sylvester’s proposals would do just that.